If you’ve worked in the Building Automation Systems (BAS) industry, you’ve probably heard of LonWorks, BACnet, and Modbus. These three open system networking technologies have been the foundation of most building automation systems over the last decade. They allow devices from different manufacturers to communicate data without issue (most of the time) so that a building’s chiller, boiler, and pumps may all work together as one system to give a building owner an integrated system that enables a high level of functionality.

I’ve seen an industry trend towards more installations of BACnet devices over LonWorks. That being said there are still a lot of LonWorks installations out there - and with good reason. Unlike BACnet, which is just a protocol that runs on top of other existing electrical standards like RS-485, LonWorks was engineered to be both a data protocol and an electrical standard for digital communications. I will be comparing BACnet to LonWorks and providing a very basic description of both their data structures.

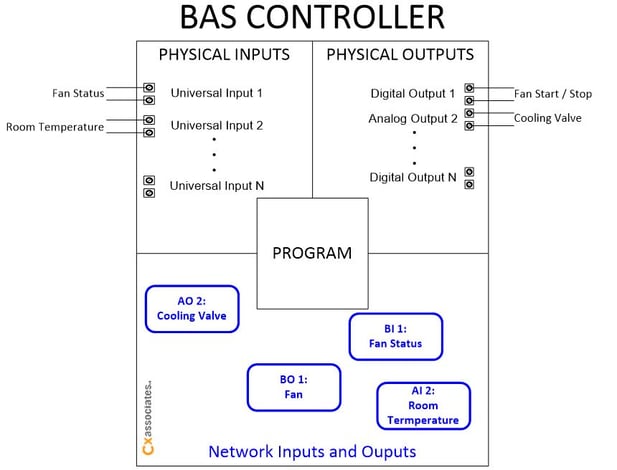

The Conceptual BAS Controller

All BAS controllers can be divided into five parts: physical inputs, physical outputs, network inputs, network outputs, and the program. The physical inputs/outputs (or I/O) are straightforward - these consist of the devices used to sense the building’s current environmental state and their wiring. The controller also commands the wiring to the devices, such as fans, pumps, and valves. The network I/O is used for global sharing of sensed and calculated information as well as receiving commands from the building’s operators (like set points and occupancy schedules). The program is what generates the output signals based on the sensor inputs, network data, and the engineered sequence of operations (or how the equipment should behave automatically).

This model is an example of a BACnet controller:

BACnet communicates using a series of data “objects” that are, for the most part, pretty similar to how everyday people think about their data. These objects are simple chunks of data representing the data inside a BAS controller. Anytime someone comes across an “AI” object in BACnet, it’s pretty safe to assume this is an Analog Input on the controller. The same goes for BI (Binary Inputs), AO (Analog Outputs), and BO (or Binary Outputs) objects. Seems pretty easy right?

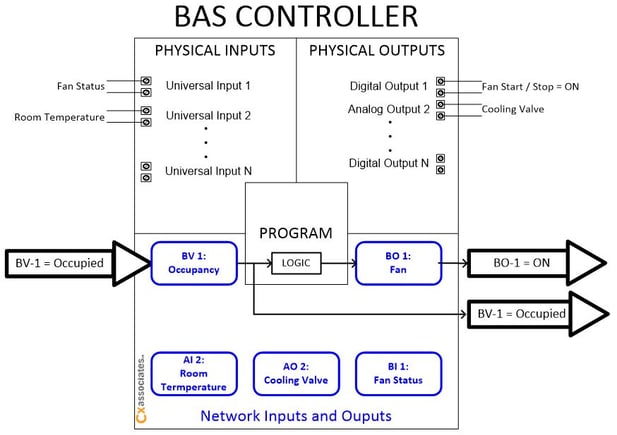

In BACnet most network “Objects” are bidirectional, which means they can be both a network input and output at the same time. For example, if an air handling unit in your building received a signal to go occupied, this signal would be sent over the network on a BACnet binary variable (or BV). This would then cause the fan to turn on (and anything else logically that needs to happen). The same BV that is used to send the controller the occupancy command is also read from the controller to see if the controller actually received the command and went occupied:

This is part of what makes BACnet so easy to use and understand. The only limitation is in how well a particular controls manufacturer has stuck to the BACnet specification (ASHRAE Standard 135) since full compliance is voluntary (but beneficial to having a good product).

LonWorks Provides More Granularity

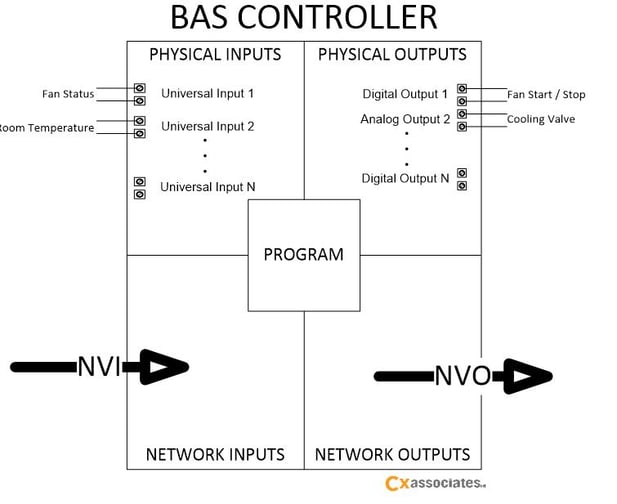

Just like BACnet, LonWorks also breaks its data in to discrete objects. These objects are called standard network variable types, or SNVTs (pronounced “sniv-its”). What is a SNVT? SNVTs are directional, which means they’re either a network input or an output. These are called Network Variable Inputs (or SNVT_NVI) and Network Variable Outputs (SNVT_NVO).

Inputs can only be connected (or in LonWorks terminology “bound”) to outputs and vice versa. There is also a special type of SNVT called a Configuration Input, which is an input that is not meant to be connected to another SNVT because it is used only to configure the BAS controller program.

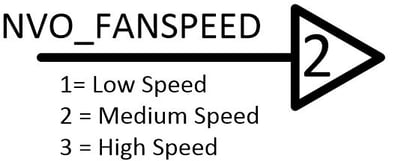

SNVTs also have three types: Simple, Structured, and Enumerated. Simple SNVTs are the type which holds only one piece of information. Enumerated SNVTs take a list of values and assign a number to each item in the list. The list is known on both devices, so only the number is sent across the network. An example of this is fan speed switches where they’re either low, medium, or high speed. So the enumeration would look like this:

By just sending a 1, 2, or 3 over the network, we save on data traffic. Currently as shown above, the value is a 2 for medium speed.

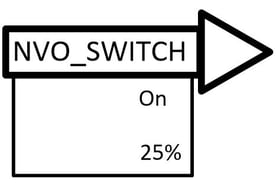

Structured SNVTs are just a combination of simple and enumerated SNVTs grouped together. If we wanted to send the information about a light switch with a dimmer in a SNVT, we might use a SNVT Object called a “Switch” and it would be a structured SNVT containing both a simple SNVT holding the “On/Off” value of the switch and another simple SNVT with a value for the dimmer in “% Dimmed.”

As you can see this is one SNVT carrying two pieces of data. The advantage is that only one network message (called a packet) goes out carrying both pieces of data regarding the entire state of this light switch. There are a lot of structured SNVTs and you can think of them as just groups of data that are relevant to a piece of equipment or a particular sequence of operations.

As you can see this is one SNVT carrying two pieces of data. The advantage is that only one network message (called a packet) goes out carrying both pieces of data regarding the entire state of this light switch. There are a lot of structured SNVTs and you can think of them as just groups of data that are relevant to a piece of equipment or a particular sequence of operations.

Some Rules for Planning a Lon Network

To start planning Lon networks, you must know some simple rules.

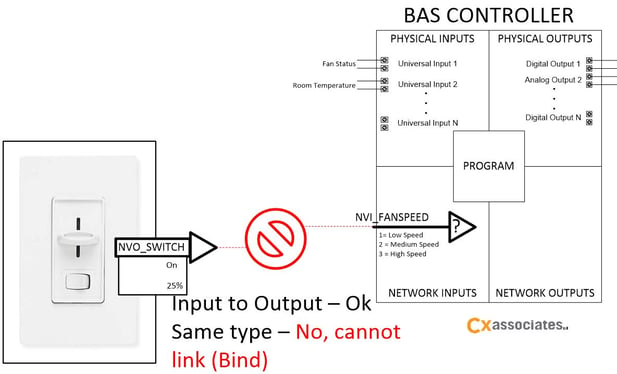

- NVIs must be connected only to NVOs

- Only SNVTs of the same type (same structure with the same data) can be connected to each other.

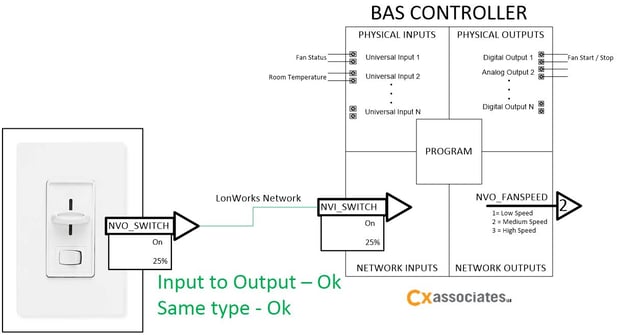

So given our light switch example below:

These two devices will talk (the light switch and the BAS controller) because we have the same structured SNVT on both sides, one as an output and one as an input. But if our BAS controller only had the FanSpeed enumerated SNVT as its only free NVI, it wouldn’t work because we cannot have our light switch inform fan speed:

This structured mix and match makes sure that the data you want to send is compartmentalized and tailored to your application on a data structure level. The intent was to optimize traffic by grouping related data together and providing manufactures with a toolbox of perfect fit SNVTs for their applications. This toolbox, called the SNVT master list, contains 90 pages of data structures.

Once two SNVTs are properly bound, they will communicate forever between the two devices (as long as they have power and an undamaged Lon connection). This is about as peer to peer as communications can get as neither device controls the network more than the other. In contrast BACnet uses a talking stick type approach over most of its implementation and uses the same set of 18 objects for everything in a more simplistic approach. There are more than 18 objects in the BACNet standard but most integrations use about 10.

Obviously this is just a brief overview of what SNVTs are, and how they’re structured in contrast to BACnet objects. In my experience, LonWorks is a very good, reliable system for communications that has many benefits that may not be immediately obvious to many systems integrators. BACnet may be winning the market because of its software-side ease of use, but that shouldn’t make anyone feel they got a bum system if they’re using Lon. For more information, feel free to drop a comment here with a question or contact Cx Associates directly.