Benchmarking is on my mind. I've been reviewing the project submissions for the Vermont’s Greenest Buildings Awards and am so impressed by what some teams are achieving in designing and operating energy efficient buildings that use far less than “typical” buildings. The only way we can know how good (or bad) our buildings are is to benchmark them. Benchmarking is a process where we calculate the annual energy intensity (kbtu/sf/yr) – adjusted to reflect weather variations from “normal” which is known as “normalizing” the data for weather. This number is like the building’s miles per gallon and can be used to find out whether the building is an energy sipping hybrid, a typical mid-sized sedan or a guzzling SUV.

I’m going to share a little about the projects submitted for the awards starting with residential. But first, I’ll share the results of my own home benchmarking exercise.

Residential Benchmarking

On the positive side, my home is designed to be passive solar, has 6” studs and when we replaced our boiler a few years ago, we put in an energy efficient low mass oil boiler with indirect fired hot water. And, the house is reasonably well controlled with four separate heating thermostats. Seems like we shouldn't be too bad, right?

The negative side is – the house has a deteriorating shell and failed windows resulting in drafts and radiant discomfort in the winter driving the heating set-point higher in occupied areas, a damp basement with air quality issues, R-19 fiberglass insulation in the attic and an uninsulated foundation. How bad are the energy impacts of these known failings?

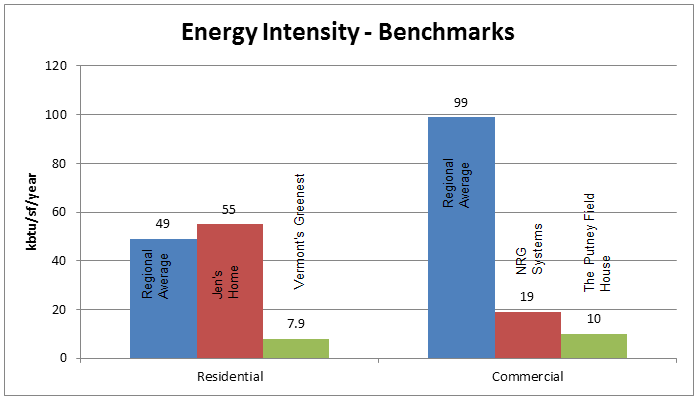

Our energy consumption includes oil and wood for heating, propane for cooking and electricity for everything else. I did a rough calculation and found that my home’s normalized EUI is 55 kbtu/sf/year. While we have no dryer and efficient lighting and appliances – our home uses more than the regional average for homes which is 49 kbtu/sf/year. In contrast, The Charlotte House, designed by David Pill and winner of a Vermont’s Greenest Building Award has an energy intensity of less than 8 kbtu/sf/year! When the solar and wind energy from the site is factored in, the home is a net energy generator (it makes more energy than it uses). Looks like I have a lot of work to do. And while I knew it before, doing the math makes the problem glaringly apparent.

Commercial Benchmarks

There is far greater variety in commercial building types and two buildings with very different occupancies had extremely low energy intensity. NRG Systems of Hinesburg, Vermont submitted both the original building and addition with an energy intensity of about 19 kbtu/sf. This is truly remarkable for a state of the art facility that houses offices with significant data processing requirements, light manufacturing, warehouse and a variety of employee amenities. The commercial building recipient of the Vermont’s Greenest Building Award is The Putney School Field House which uses only 10 kbtu/sf/year and also produces more energy on site than it consumes making it another net energy generator. The occupancy is likely lower as are the need for computers and other systems essential to a facility like NRG Systems. These remarkably successful projects have key team members in common – William Maclay Architects and Energy Balance working on the approach to efficiency.

These projects demonstrate what can be achieved and give us a goal to which we must aspire. They provide the needed amenities, allowing people to work and live comfortably and do so while actually providing a net benefit to the planet. If we all start benchmarking our homes and businesses, we will learn where we fall on the scale and we can begin our energy diet by finding and implementing energy efficiency measures. This will help us bring our energy intensity down to the point, where like the awardees, we may be able to use renewable sources to generate more energy than we consume on our building sites.